Let’s take a deeper look at the thermodynamics. In particular, we can examine the relationship between the enthalpy and the temperature during phase transitions.

Remember, heat can be tricky. When there is no chemistry or phase transitions, then energy flowing into a system in the form of heat will lead to a temperature change. However, when there is chemistry or a phase transition, then energy will flow in and the temperature can stay constant. Why doesn’t the temperature go up? This is because the energy coming in results in higher potential energy and not higher kinetic energy. What is the higher potential energy in this case? It is the new state formed after the breaking up the IMFs between the molecules. Liquid water at 0 °C has a higher potential energy (enthalpy) than the same amount of ice at 0 °C.

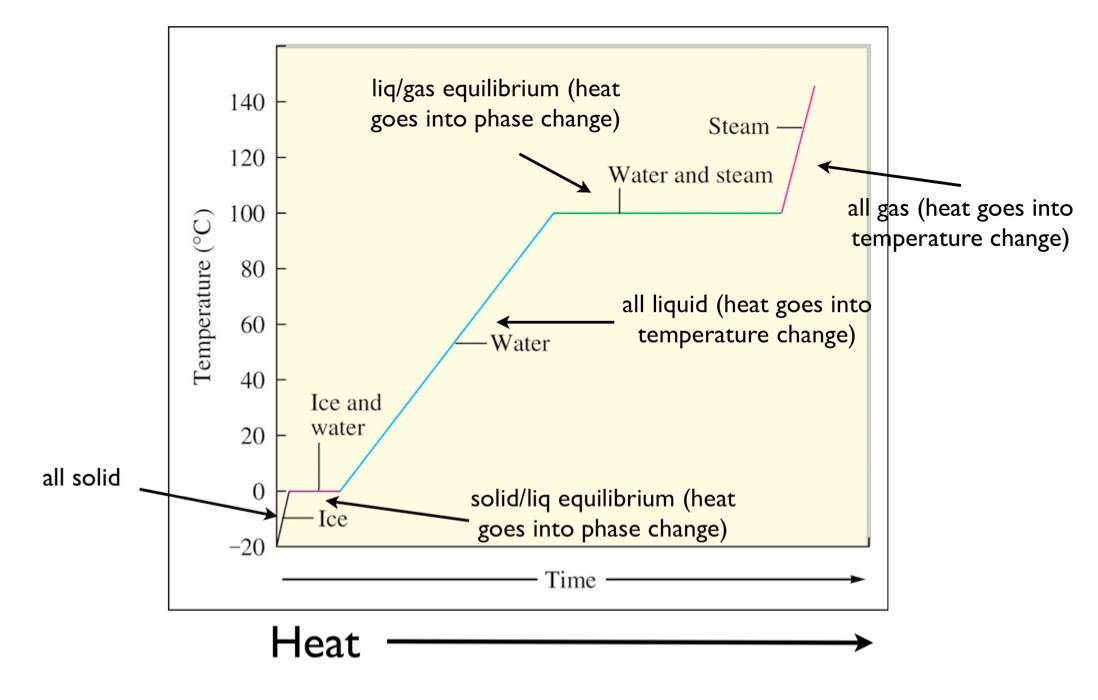

This can be easily seen in a heating curve that plots the temperature of a system as a function of the heat flow into the system. Initially the system is a solid, then it has a melting transition, then it is a liquid, then has a vaporization transition, and then it is a gas. This is shown in the heating curve below for water. Initially, the system is solid water. As the heat flows in, the temperature of the ice increases.

The slope of this line is inversely related to the heat capacity of solid water (ice). Since this is at constant pressure \(q = \Delta H = mC\Delta T\). For those who have forgotten, q is the heat, m is the mass, C is the specific heat capacity, and \(\Delta T\) the change in the temperature. As this graph is a plot of T vs q, the slope is actually 1/mC.

As the heating continues, the solid melts. During this time the temperature is constant. The length of the line is the amount of heat required to melt the solid. This amount of heat is the enthalpy of fusion (\(\Delta H_{\rm fus}\)). \(\Delta H_{\rm fus}\) usually has units of kJ mol-1, thus the actual length of line will be n \(\Delta H_{\rm fus}\) since you’ll need to multiply by the number of moles of solid to get the total heat of the phase transition.

After all the solid melts, the temperature will then start to increase again. The slope of this line is again inversely related to the heat capacity. However, this time it is the heat capacity of the liquid (water). Once the boiling point is reached, the temperature will again be constant thoughout the vaporization transition. After all the liquid vaporizes, the temperature will increase again and the slope of the line will be inversely related to the heat capacity of the gas.

© 2013 mccord/vandenbout/labrake